Market Update: Recession risk and the audacity of hope Posted on June 17, 2022

Article by Matt Sherwood, Head of Investment Strategy, Multi Asset @ Perpetual

Summary

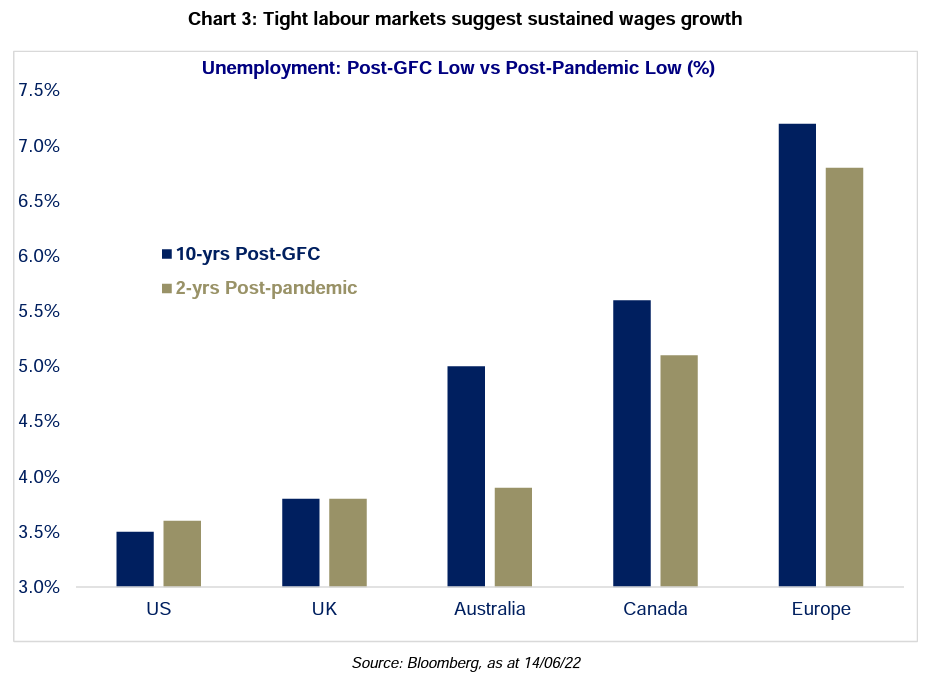

- Only a few weeks ago there was a “hope trade” in markets that the Fed will back off the rate hikes in the September quarter. However, extremely high inflation, very low unemployment, and very late policy tightening means central banks are not in a position to pivot on policy and bail out markets like the Fed did in 2016 and 2018. This would only occur if they have made a mistake as evidenced by a sharp slowing of economic growth or the S&P 500 declining through 3,500. Neither of these are evident at present, and central banks need to continue moving rates higher to lessen the heat from very tight labour markets.

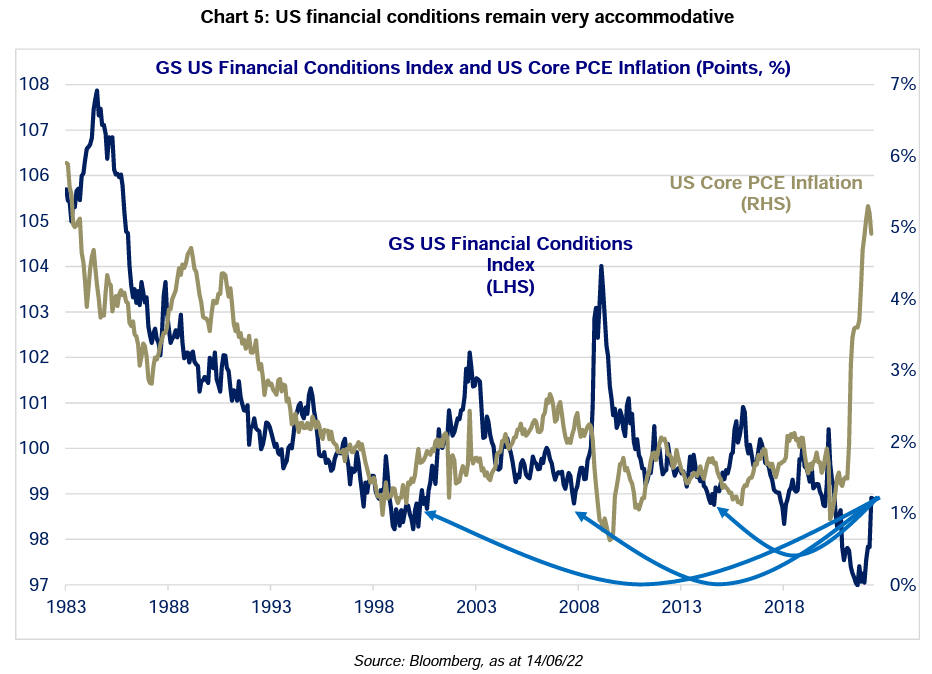

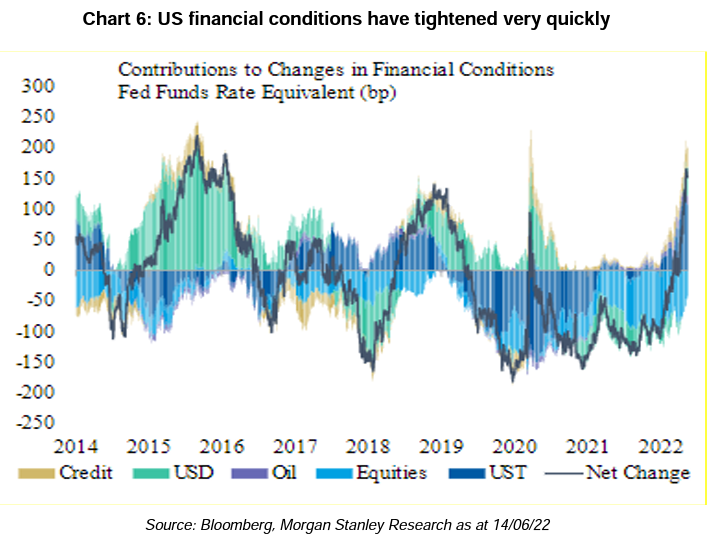

- Although fiscal and monetary stimulus is finally being wound back, a major misalignment persists between 40-yr highs in inflation, 40-yr lows in unemployment and real interest rates close to historic lows. Central banks are well behind the curve, but Morgan Stanley estimates that the tightening in US financial condition in the past six months is equivalent to 2.5% in Fed Funds equivalent terms, albeit from incredibly low levels. However, over the past 25 years financial condition at current levels have not sparked a material decline in inflation in the subsequent two years outside the severe recession which occurred during the 2008/09 GFC. This suggests that firstly rates need to go materially higher and, secondly that the Fed does not have the optionality to pause.

- The key for markets and investors moving forward is what happens to inflation, and there is no clear path here, but at present real cash rates are far too low to see core inflation back at 2% within the next few years. There is considerable cashflow pain ahead for households given higher energy and food prices, in addition to central banks having to tighten policy to get growth materially sub-trend. This is needed to have inflation within the realm of the typical 2% target by 2024, and rate hikes this year will weigh on activity in 2023 where recession risks seem much higher than what they are for the remainder of this year.

A challenging macro backdrop

It is the best of times; it is the worst of times. While unemployment in most advanced economies is at 30 or 40-year lows and wages growth is on the rise, disposable income is being squeezed by multi-faceted supply side inflation which acts like a tax on discretionary spending. The last time regional inflation was this high occurred in the early 1980s after oil prices tripled to $US40 a barrel in the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. While the energy price gains after both the 2020 pandemic and 2022 Ukraine invasion have been more in Dollar terms, the negative impact on inflation and spending is considerably less.

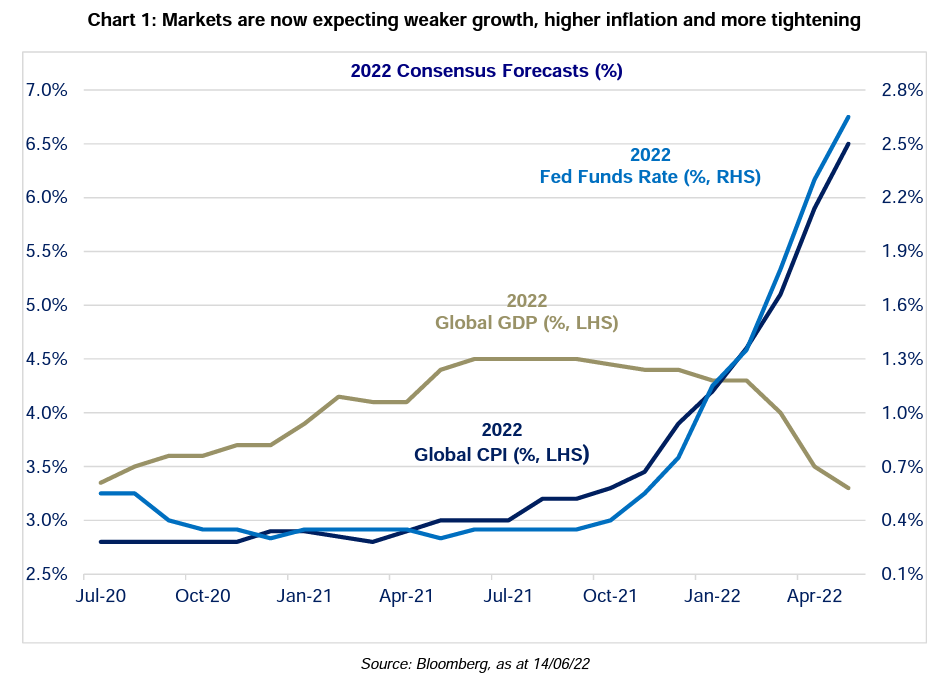

Investors were upbeat about macro prospects coming into 2022 with forecasts for above-trend global GDP growth and inflation remaining close to the typical 2% target with modest policy tightening. These forecasts have been heavily revised in the subsequent five months with global growth downgraded by -1.2%, and global inflation upgraded by +2.1% which has sparked a tripling of US Fed Funds rate expectations to +2.4% (Chart 1). All three of these expectation changes negatively impact asset prices with slower GDP growth reducing corporate revenue growth, increased input costs weighing on margins, and higher interest rates sparking lower valuations. Assets markets have responded to the change in circumstances with losses in regional equity markets, widening spreads in credit markets and capital losses in government bond markets. Moving forward a lot hinges on how successful central banks are in materially lowering inflation without causing a recession.

From stagnation to stagflation?

In the past two years a lot of what investors took for granted has unravelled which has raised questions about the path forward. In particular, global supply chains have experienced on-going Covid-disruptions, geopolitical tensions have sparked an end to the peace dividend, shortages of energy supplies now seem endemic and corporate stalwarts such as Amazon and Walmart are issuing profit warnings, and Target has issued two warnings within five weeks. Despite the many cross currents, the key challenge for markets is inflation being two or three times above the typical 2% target level. Some have called this ‘stagflation’ which was an economic disease of the 1970s characterised by below-average growth, high inflation, and very high unemployment. While only one of those factors is evident today, four issues remain challenges in relation to consumer prices:

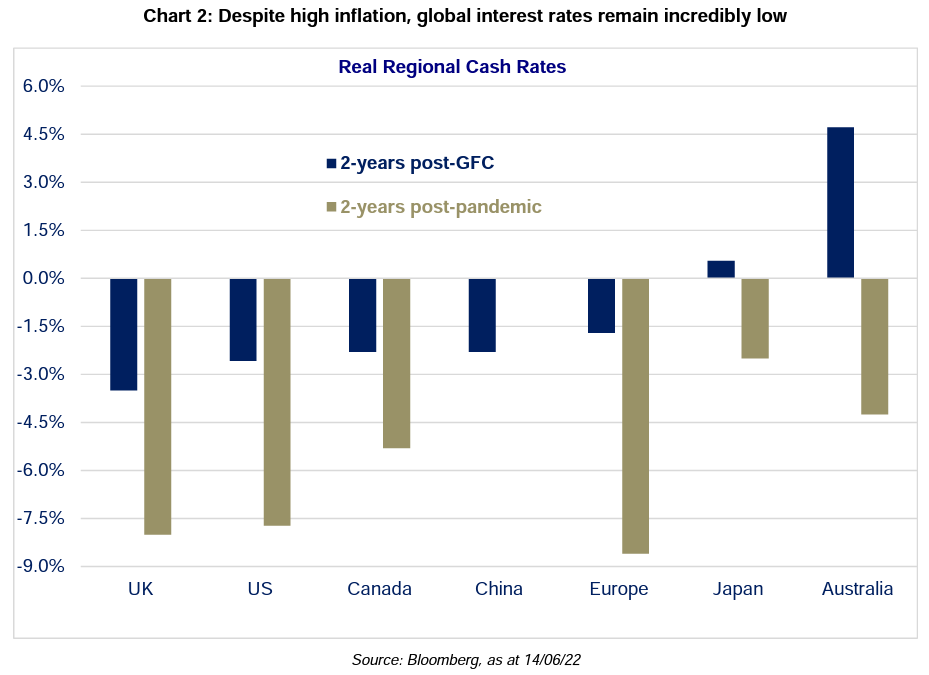

- Extremely low real interest rates – Global inflation has been above pre-pandemic levels for 14 months (and is now triple the headline level in January 2020), yet real policy rates remain twice as low as the equivalent stage of the post-GFC cycle (Chart 2). Back then negative real rates were required given the 8 years needed for both widespread private and public sector deleveraging, and to facilitate a complete recovery of respective labour markets. Today’s deeply negative real rates are simply not appropriate for a 40-yr high in inflation and central banks will need to remove accommodation quickly if they want 2% core inflation to be something else other than a memory;

- Tight labour markets – A key misjudgement by central banks post the 2020 Covid recession was the expectation of a sustained dislocation in the labour market. While it took around 8 years for regional labour markets to recover the unemployment lows after the GFC, it has taken just two years in the current cycle (Chart 3). More importantly, in the US the number of job openings is twice the size of unemployed US workers. On the positive side, this has seen wages growth bid up to provide some income relief from elevated inflation. However, there is also a high risk of this imbalance creating the positive reinforcing feedback loop which characterised the 1970s (where high inflation sparked higher wages, which fed back in higher consumer prices as firms sort to recover cost increases) and this link needs to be severed for central banks to have any chance of having core inflation anywhere near +2% by 2024;

- Deglobalisation – the trade war between the US and China in recent years highlighted the relative decline in living standards that globalisation forced onto lower income workers in Western economies. Meanwhile, the Covid-pandemic and the 2022 Ukraine war have exposed the basic fragilities of globalised supply chains. While trade in food and energy between countries is required as domestic supply comes down to natural endowments, the global goods disruption from China’s zero-Covid policy seems an own goal. This has, in turn, seemingly sparked increased discussion within some corporations to focus more on supply security than cost efficiency, which in the absence of a major rise in productivity, would be highly inflationary; and

- Decarbonisation – the desire to reduce fossil fuel emissions has sparked a major investment decline for energy and materials companies which, in turn, has reduced industry spare capacity. This tight supply-demand balance has meant that any interruption to production nowadays spark a major rise in raw materials prices. The onset of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the subsequent trade embargoes from Europe, saw not only global commodity prices spike higher and increased fears about higher global food prices, but also increased demand for fossil fuels as there is not yet widespread spare capacity in renewables. The move to decarbonisation will lead to higher energy prices at least during the transition stage, which will increase prices for one of the two key inputs to the global economy (i.e., energy, with the other being labour).

The four points above suggest that the 2020s risks being the most inflationary decade since the 1970s, but in the early stages of this cycle the sharp increase in core inflation has primarily flowed from excessive postpandemic stimulus, rigidities in regional supply chains (both commodities and components) and prolonged closure of the services sector (which sparked increased demand for goods). While these three issues should ultimately be resolved, the source of inflation could soon switch from impaired commodity and component markets to extremely tight labour markets, and this impact will likely be reinforced by prolonged price increases from deglobalisation and decarbonisation.

A key question for investors

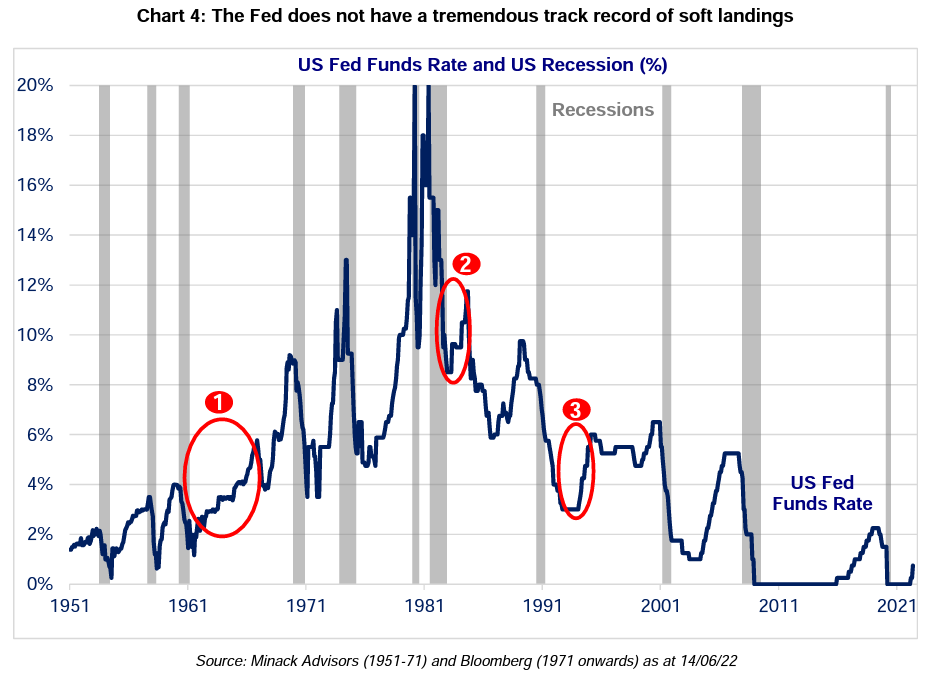

Given the backdrop, a key question for financial markets and investors is whether central banks can actually tighten policy to get core inflation back to 2% without causing a recession. Despite Chair Powell’s suggestion to the contrary, the Fed is not renowned for its ‘soft touch’ with its prior 14 tightening cycles sparking 11 recessions within the next two years (Chart 4). Even if it is rightly argued that the recession of 2020 was sparked by the pandemic rather than policy tightening from 2015-18, 10 recessions from the remaining 13 tightening cycles is still an underwhelming success rate.

Any assessment of global growth prospects must incorporate an assessment of all policy reaction functions, and in contrast to the last two economic cycles, fiscal policy has moved in the direction of providing some offset to the income squeeze. Clearly nowadays governments are not being punished for poor fiscal management through materially higher interest rates, and while this could enable them to provide targeted relief to lower income earners, they need to be guarded to not exacerbate the inflation problem through poorly designed policy initiatives.

Financial conditions – tightening, but not tight

Increases in the Fed Funds Rate so far in 2022, combined with hawkish guidance, has had a financial market impact, and sparked tighter US financial conditions. However relative to history, financial conditions remain quite accommodative given they are at levels which are equivalent to the lows of the prior three business cycles (i.e., the levels seen in 1999, 2007, and 2018). The subsequent two-year change in US core PCE inflation after these three occasions was the most significant in 2007/09 (-1.3%) which was the worst economic dislocation since 1946 in terms of lost production over an extended period of time. In contrast, on the other two occasions the US economy only contracted for a handful of months, and core PCE inflation actually rose +0.1% in the subsequent two years. Consequently, history suggests that if the US Fed is serious about maintaining their inflation credibility, financial conditions need to tighten considerably more.

The central bank challenge

Morgan Stanley (MS) estimates that the tightening in US financial conditions since the start of 2022 is a bit under +2.5% in Fed Funds equivalent terms, with the rise dominated by the increase in bond yields and the widening of credit spreads (Chart 6). Interestingly, the Fed has guided the market that its’ estimate of the US neutral interest rate is 2.5%, and it wants to get there quickly before deciding on how much additional tightening is needed. On that basis, it seems that the markets are simply reacting to the Fed’s communication. However, the speed of adjustment here is just as important as the magnitude and MS estimates that the total tightening is a bit less than the total that occurred in 2015/16 and 2018 but it’s occurred at a faster pace – namely, +1.6 bpts of tightening per day in 2022 relative to +1.1 bpts and +1.4bpts, respectively in the two previous occasions. Importantly, after hiking rates once in 2015 the Fed paused for 12 months, and 9 months after reaching its terminal rate in 2018 it was easing policy. On both occasions core PCE inflation was below +2% which gave the FOMC the necessary room to stop leaning on the economy, but in 2022 and 2023 inflation will remain quite high, so they most likely won’t have that luxury.

Recession risks

Throughout history recessions have emanated from three broad groups in the 1970s or Cov-– shocks (such as wars, the oil crisis 19 in the 2020s), financial crises (the GFC) or a policy mistake. Over the course of the past six months, US and global growth has been resilient to the income squeeze from sharp rises in supply side inflation which suggests that a much larger shock would be needed to spark a recession in 2022. Among other things, the recent growth resilience has been underpinned by strong employment gains and lower household savings, but there is now scant labour market spare capacity to reemploy, and savings are becoming depleted particularly in the US (but less so in other major economies). This suggests growth is set to materially slow in the period ahead.

The key for markets and investors moving forward is what happens to inflation, and there is no clear path here, but at present real cash rates are too low to see core inflation back at 2% within the next two years. While global growth is moderating from a strong above trend pace, the driver of inflation is changing from very high commodity prices to very tight labour markets, which is sparking very aggressive rate increases, and it is this which threatens an early end to the expansion. The risk of a ‘policy late, significant, and rapid mistake’ increases if policy removal is , and in many ways central banks are probably not in a world of good choices anymore. Worryingly inflation is at 40-year highs and the policy withdrawal in numerous countries including the US and Australia is the fastest in nearly 30 years and the world is a lot more indebted than was the case back then. Robust labour markets, a solid state of global private sector balance sheets, still low rates today and positive, but depleting, household savings suggests that recession risks are lower in the next 12 months, than for 12 months after that where they are very material. At this time, savings will be fully absorbed, and higher interest rates will be impacting activity.

Markets may hope that the Fed pauses its tightening cycle in September, but quite honestly, I don’t see it. A subsequent note out within the next month will examine, the risk market outlook in the prevailing economic terrain, and the portfolio implications for investors of tightening policy and slowing growth.